Novel microscopy and chemoprevention strategies combat skin cancer

May is Skin Cancer Awareness Month, and our BIO5 researchers are working to better prevent and diagnose this highly prevalent cancer.

Residents of the sunniest state – Arizona – are no strangers to ample sunshine. While sun exposure is beneficial to our wellbeing, it’s also a major cause of skin cancer, the most common type of cancer in the U.S. At least 5 million people in our country are treated for skin cancer annually, resulting in more than $8 billion in medical expenses.

Skin cancer is caused by exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, most often from the sun or tanning beds. UV light is invisible, but it penetrates the skin and harms cells by damaging genetic material, DNA. When sufficient DNA damage accumulates without repair, mutated cells uncontrollably grow and transform into cancer.

The most common types of skin cancer are basal and squamous cell carcinomas and melanoma. Basal and squamous cell cancers are named for the lowermost actively dividing cells and the uppermost cells in the skin, respectively. They comprise most skin cancers and affect areas on the body often exposed to the sun. While quite common, these skin cancers are usually treatable.

Melanoma is named for malignant melanocytes – the cells that give rise to skin pigment. These cancers are often found on the chest and back in men and legs in women, as well as the neck and face. Though more rare than basal and squamous cell carcinomas, melanomas are highly metastatic. Because of their high propensity to spread throughout the body, melanomas are difficult to treat and sometimes lethal.

Skin cancer can be identified with the ABCDE method – asymmetrical, irregular border, multiple colors, larger than 6 millimeters in diameter, and visually evolving. If a lesion fits these criteria, a biopsy is usually assessed for molecular and/or genetic changes to confirm the diagnosis.

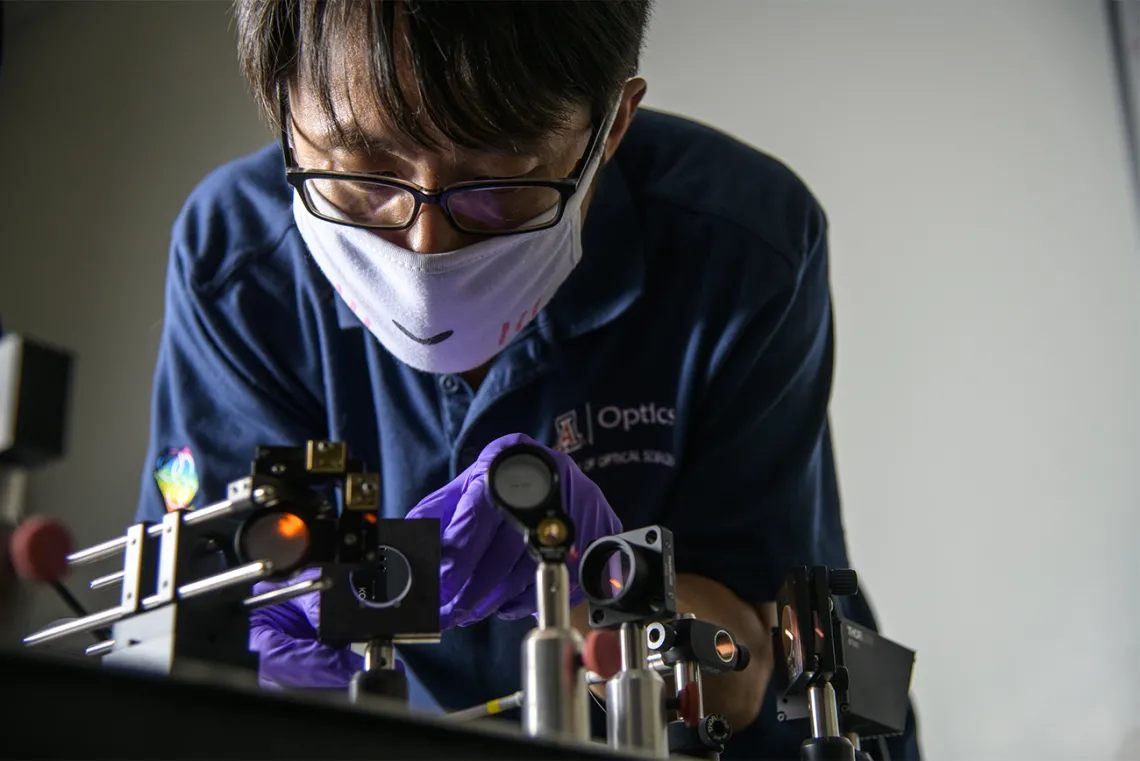

Dongkyun Kang, assistant professor of biomedical engineering and optical sciences, is developing a low-cost smartphone microscopy device that can visualize cellular details to help diagnose and treat skin cancer. This technology will enable easier detection both in low-resource and large population settings.

Kang is also collaborating with Clara Curiel, director of the Pigmented Lesion Clinic and the cutaneous oncology program at the UArizona Skin Cancer Institute, on a reflectance confocal microscope that allows doctors to quickly and safely diagnose skin cancers and monitor treatment responses without a biopsy.

As with all cancers, there is no cure for skin cancer. Surgery, cryotherapy, radiation, and therapeutics including chemotherapy and immunotherapy are common treatment modalities, however, scientists and physicians urge that prevention is key to battling skin cancer.

The simplest way to prevent skin cancer is to limit UV exposure. The UArizona Skin Cancer Institute recommends the ACE plan:

Avoid excessive UV exposure

-Limit sun exposure from 10 A.M. to 4 P.M.

-When outside, seek shade

-Avoid burns and tans from the sun and tanning beds

-Avoid exposure to reflective surfaces such as water, glass and concrete

Cover up

-Wear long sleeved shirts and long pants, a wide-brimmed hat, and sunglasses that block 99-100% of UVA/UVB rays

-Use a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 30+ and a lip balm with SPF

Examine your skin regularly

-Look at your skin once a month for new or changing spots/moles

-Have your healthcare provider check your skin regularly

Any change to skin color – from a light tan to a bright red sunburn – indicates skin damage that has the potential to contribute to cancer over time.

Curiel, also the interim chief of dermatology at the College of Medicine – Tucson, studies chemoprevention as a method to slow, stop or reverse the progression of skin cancer. Dietary means, natural or synthetic agents (like aspirin), and vitamins (particularly vitamin A) are used to thwart carcinogenesis. Unlike sunscreen, which blocks initial UV damage, chemopreventative agents target damaged areas of the skin and prevent disease progression.

The physician-scientist is also developing new strategies to prevent and reduce the risk of squamous cell carcinoma. She and a team of researchers at the UArizona Cancer Center were awarded $6.9 million from the National Cancer Institute to assess the importance of an innate immune receptor, TLR4, which is often modulated by UV radiation. Dr. Curiel-Lewandrowski and colleagues are also characterizing a cascade of recently discovered cellular messages that promote skin cancer development after sun exposure.

Ultimately, her work will help to inform the formulation and testing of topical drugs, like lotions and creams, that target these messages to ultimately to prevent squamous cell cancer formation.