Leading by example: A community of support for women and girls in science

Heddwen Brooks provides career guidance and compassion to help females pursue both motherhood and an outstanding career.

One of the most challenging barriers women and young girls face in science is the bias that they can either be career- or family-driven – not both. In fact, a 2019 study found that more than 40% of women with full-time jobs in science leave or transition to part-time after having their first child, in contrast to less than one-quarter of new fathers.

Heddwen Brooks, professor of physiology and biomedical engineering and member of the BIO5 Institute, is a successful scientific researcher, professor, and journal editor who not only has a daughter herself, but also creates a lab community in which young girls and women can flourish in their pursuit of this dual role.

“Seeing is believing, so for me it was important to show others that you can balance science and a busy family life. Too many women leave science, perhaps as they don’t have mentors to help them with their vision of success or to talk to when they need assistance in creating a flexible workplace. My trainees have seen me take my daughter to scientific conferences at three months old - and many more since. I share my failures and successes, as I hope it helps others know they can also work through life’s challenges,” says Brooks, who is also an associate professor of pharmacology and the co-director for the new Bachelor of Science in Medicine program.

From zoology to hypertension – Brooks’ journey to science

Brooks’ passion for science stems from high school, where biology was one of the few subjects she fell in love with. In college, she studied zoology and got a taste of research with a brief parasitology project before traveling to Ghana, West Africa, for a year to teach science to 11- to 18-year-old girls. She taught everything from photosynthesis to the human body using one textbook and a chalkboard to classes of more than 50 girls. Despite sparce resources, Brooks was enamored by the girls’ curiosity and enthusiasm.

“Their passion for science was absolutely incredible,” Brooks said.

Growing up as a girl in Wales, the expectation to attend University wasn’t high. After completing a degree in zoology surrounded by male peers and professors, she pursued a master’s in parasitology and doctorate in molecular biology in the UK. When Brooks came to the University of Arizona for a postdoctoral fellowship in 1997, she was awestruck to be surrounded by women.

“The biggest thing that struck me about the University of Arizona was the number of women faculty in the physiology and neuroscience departments,” she said. “I was amazed by the opportunities that women in the U.S. had to lead research groups.”

In 2001 following a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, Brooks secured a faculty position at UArizona and not soon after gave birth to her daughter. To maintain what she calls “work-life flexibility,” Brooks learned to set clear boundaries throughout her academic career, prioritizing time for her daughter’s activities, be it sporting events or homework. This meant work often happened at night or on weekends. Brooks’ ability to navigate being both a mother and a budding faculty member garnered attention.

“Once you become a faculty member and have a child, it attracts other women,” she said. “They see you doing both, so they feel like they can, too.”

Brooks not only continues to serve as a role model for her peers, but she also surrounds herself with strong women who can mentor and empower her.

“I’ve been lucky to be mentored by women for the last 20 years,” she says. “Female mentors are fantastic because they push you to be brave in applying for awards and different positions, even if you don’t get them the first time. They really encourage you to never give up.”

Merry Lindsey, the Chair of Cellular and Integrative Physiology at the University of Nebraska Medical College, serves as Brooks’ journal mentor and friend. Lindsey nudged Brooks towards her current role as the Editor in Chief of the American Journal of Physiology – Renal, and in turn, Brooks supported Lindsey in becoming the Editor in Chief of the American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. Both are the first women to hold both positions.

Kim Barrett, former Dean of the University of California San Diego Graduate School, wrote a letter of recommendation for Brooks’ promotion and tenure application back in 2007 and has continued to support her career by inviting her to coauthor a textbook on medical physiology and to take leadership positions in the American Physiological Society.

UArizona Professor Emerita Patricia Hoyer helped Brooks define her research focus on the intersection of menopause and hypertension. Hoyer was also instrumental in teaching Brooks how to mentor students.

Mentoring successful women

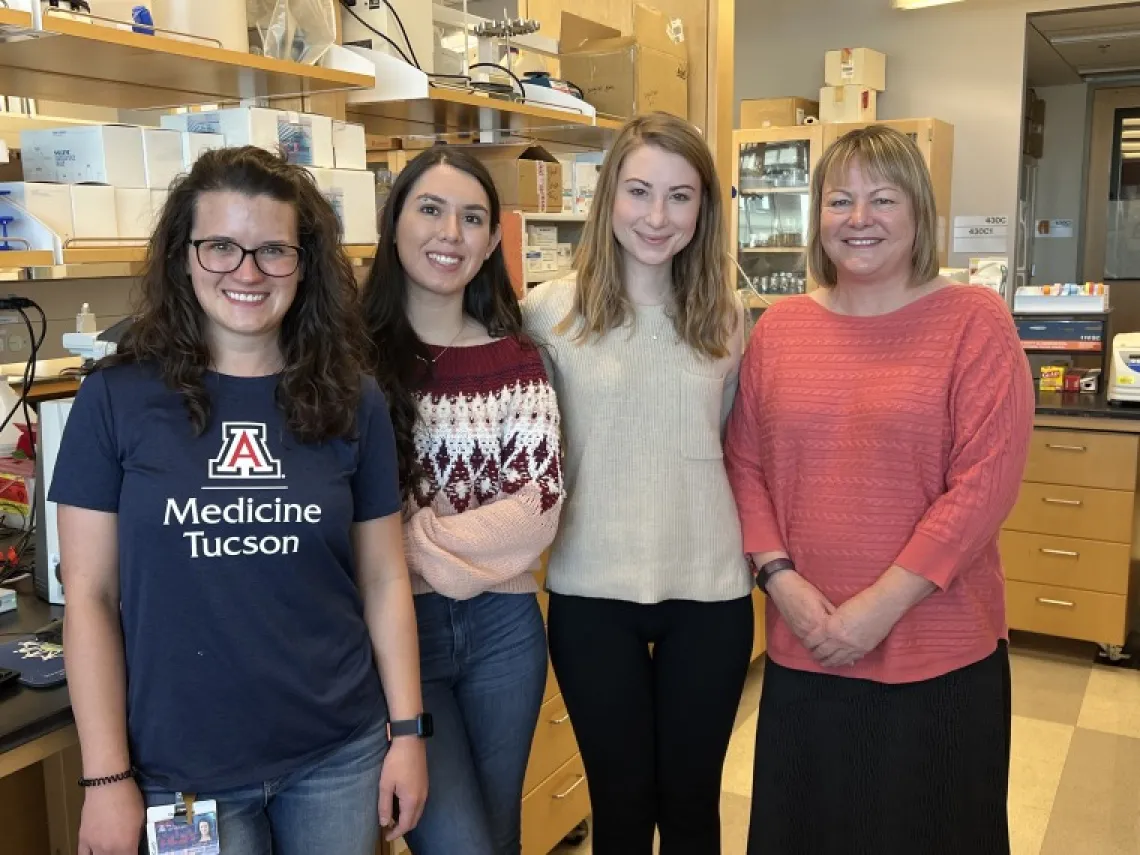

To this day, Brooks continues to be a role model to women and girls who desire to both be brilliant scientists and mothers. She has not only empowered her female colleagues, but she’s created a community of support within her laboratory. In the last two decades, Brooks has mentored over 50 women, including KEYS high school students and UArizona undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs, and lab managers. She is also proud to have eight “lab babies,” including her own.

“With my students that are interested in having children, I always make it a point to address the ‘elephant in the room’,” she says. “There’s no perfect time to have a family – things will change in their careers – but I will be by their side to work it out so they can graduate and progress in their careers.”

One of Brooks’ earliest students, Jill Romero-Aleshire, truly benefitted from Brooks’ dedication to supporting strong career women and mothers. Beginning in the lab as a master’s student in 2004, Brooks not only coached Romero-Aleshire through navigating graduate school and writing a thesis, but she was also supportive when Romero-Aleshire had her daughter a year and a half into the program.

Jill Romero-Aleshire with Heddwen Brooks at her Master's defense

Following her master’s, Romero-Aleshire worked in the lab as Research Specialist for 13 “incredibly gratifying years” during which she gave birth to her son. Brooks also supported Romero-Aleshire in her most recent role as an Assistant Scientific Investigator as she pursued her PharmD at UArizona, which has ultimately led to her current position as a Clinical Research Pharmacist in Charge. Brooks enabled her to work in the lab around classes, rotations, and kids’ schedules – a rare, compassionate flexibility that has made a tremendous impact on Romero-Aleshire’s personal and professional life.

“I’ve always wanted a career that I could be proud of, where I could benefit others and show my kids that anything is possible with a little hard work and motivation. I was lucky that Heddwen has always mentored talented and intelligent women. Watching some of the great women she brought into the lab grow and achieve independent success served as an incubator for my own professional and social growth. There is such a tricky balance with achieving professional success and managing a family. I saw Heddwen successfully navigate those challenges and it showed me that you can be successful and also have balance. The environment that she fostered gave me so many great role models in addition to her own example, ladies like Dr. Maggie Diamond-Stanic and Dr. Qi Cai, and all of them helped me on my own path,” said Romero-Aleshire.

Brooks recently graduated MD/PhD student Megan Sylvester, who gave birth to her first daughter in the middle of both the doctoral portion of her dual degree program and the COVID-19 pandemic. Brooks not only helped Sylvester to grow as a researcher, but she also provided her with support to pursue her goals to become a mother.

Megan Sylvester

“One of the main reasons I chose UArizona for my MD/PhD training was because of the number of women in leadership positions at this university. This was the first program where I interviewed one-on-one with a woman, and it left me feeling more confident and inspired to pursue my training than ever before,” Sylvester said. “Ironically, that same woman ended up having a much larger impact on my career as she became my PhD mentor. Dr. Brooks has always pushed me to be the best scientist possible while also offering grace and guidance as I navigated pregnancy and motherhood in the midst of my PhD training. I’m not sure I fully understood how important it was to have female mentors in science until having my daughter - I can only hope to continue this cycle of support for future mentees as I start my own career in coming years.”

While most people hold the stereotype that women are less productive and focused when they become parents, Brooks disagrees, and raves about Sylvester’s positive scientific transformation after having her daughter.

“Megan really amazed me after having her daughter,” Brooks said. “She was even more focused, driven, and happy. She became incredibly goal-oriented and was able to truly enjoy the scientific research process because she witnessed herself excelling at both being a mom and a scientist.”

Training the next generation of female scientists

Both Sylvester and Brooks have served as invaluable mentors to aspiring MD/PhD student Emma Louis.

As part of her undergraduate minor in pharmacology, Louis took several classes taught by Dr. Jennifer Schnellmann, Associate Director of Undergraduate Studies in Pharmaceutical Sciences, whose passion for studying therapeutics infected Louis. The student expressed her desire to gain more experience at the lab bench, so Schnellmann connected her with Brooks. Louis joined the Brooks lab in 2020 at the end of her senior year, and she currently serves as a research technician studying sex differences in T-cell mediated hypertension.

Emma Louis

When Louis joined the lab, she considered applying to highly selective MD/PhD programs that current cycle. However, Brooks felt she needed more experience under her belt to be a competitive applicant.

“I think one of the most important things you can do as a mentor is to be honest and help people find their passion,” Brooks said. “When Emma came to me, she clearly had much talent, but she needed more experience to be a competitive applicant.”

In the last two years, Louis has gained experience both at the bench in Brooks’ lab and as medical volunteer across Africa. She’s grateful to Brooks for allowing her to explore all her options in both medicine and research so that she can find her place in the profession.

“When she told me about leaving to work in Ghana, I was incredibly supportive. She needed an adventure, a new experience, and it reminded me of my time in Africa,” said Brooks. “Since coming back, Emma is a more confident woman and scientist and is a very competitive applicant for MD/PhD programs.”

Sylvester has also served a vital role in shaping Louis’ career trajectory.

“It’s important for women to find balance between having a great career and having a family, and Megan has just that,” Louis said. “I really look up to Megan as a role model because she was not only a fantastic PhD student, but she’s an amazing, present mom. Megan has shown me that you can have both an advanced degree and family.”

When asked about what challenges she’s faced as a female pursuing a career in science and medicine, Louis says she hasn’t noticed any.

“I’m really lucky because I don’t even have to think about being a woman in science,” she said. “I’m surrounded by successful women, like Drs. Brooks, Schnellmann and Sylvester. Because of that, it’s not about who I am or what I look like. It’s about my passion for science and what I’m studying or doing.”