Shared RNA language drives ALS research at the University of Arizona

Two scientists combine complementary strengths in RNA biology and aging neuron research to advance new approaches in studying ALS, supported by the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute.

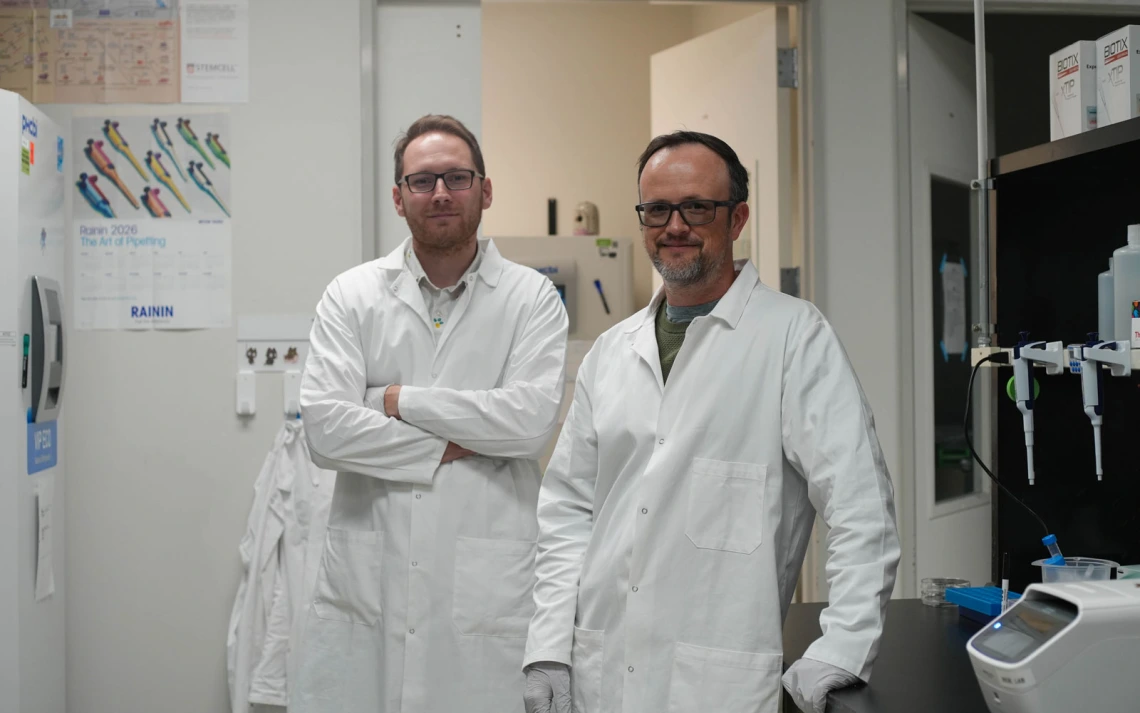

Ross Buchan (right) and Kevin Rhine (left) are using a new effort at the University of Arizona BIO5 Institute to bring faculty and clinicians together across disciplines to better understand, and ultimately treat, ALS.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

Long before they formally met at the University of Arizona, molecular biologists Ross Buchan and Kevin Rhine were circling the same question: how do cells protect their instructions under stress and what happens when that protection fails?

In neurodegenerative diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), that failure can be devastating. ALS is a progressive disease in which motor neurons that control movement gradually fail and die, leading to muscle weakness and loss of mobility over time.

For scientists, it is also one of the most difficult diseases to study, unfolding slowly over decades and rooted in subtle breakdowns inside aging neurons.

To understand why those safeguards fail in ALS, both researchers start with the same molecular system: RNA.

RNA at the center of ALS

Buchan, an associate professor of molecular and cellular biology in the College of Science, and Rhine, an assistant professor of pharmacology and toxicology in the R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy, both study RNA biology: how cells turn genetic information into action.

Ross Buchan, PhD

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

While DNA stores the cell’s instructions, RNA is the short-lived copy that allows those instructions to be used.

RNA is transcribed from individual genes and delivered to the cellular machinery that makes proteins, while also helping regulate when and where those proteins are produced.

Because proteins power nearly everything a cell does, even small mistakes in this process can have serious consequences.

Those errors are now understood to sit at the core of ALS. When cells lose control of RNA, neurons may make the wrong proteins or lose the ability to respond to stress, ultimately leading to cell damage and death.

“RNA is the most interesting biomolecule, though I’m admittedly biased,” said Buchan, a BIO5 member for over a decade.

“For decades, DNA got most of the attention,” added Rhine, a relatively new member of the BIO5 Institute. “RNA was viewed as a middle step. We now understand it plays a much bigger role in controlling genetic activity—when genes are turned on or off, and how cells respond to change."

The two labs approach RNA regulation from different angles.

Kevin Rhine, PhD

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

Rhine’s lab studies how RNA is prepared, checked, and maintained so it can be used correctly to make proteins. Buchan’s lab focuses on what happens to RNA when cells are under stress; normal protein production slows down and protective mechanisms activate.

In ALS, both of these RNA regulation systems fail. One of the clearest and most consistent examples involves TDP-43, a protein that normally stays inside the cell nucleus and helps manage how RNA is processed.

In ALS, TDP-43 ends up outside the nucleus and forms clumps in the cell, disrupting RNA regulation and interfering with how neurons respond to stress.

This abnormal behavior of TDP-43 is widely recognized as a major defining feature of ALS. Understanding what exactly goes wrong with this protein in aging neurons is a problem Buchan and Rhine were tackling separately, until now.

Modeling aging neurons in ALS

Although they had followed each other’s work for years, it was Rhine’s arrival at the University of Arizona in the fall of 2025 that created an opening for a working partnership.

“It’s very hard to study aging in the lab, because no one wants to wait for cells to get old,” said Rhine.

That challenge is central to ALS, a disease that typically emerges later in life. Many researchers rely on induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which reset adult cells back to an early, stem-cell-like state before growing them into neurons. While useful, that reset turns back the cellular clock, making it harder to model diseases in aging neurons.

Rhine leads the first lab on the University of Arizona campus—and one of only a handful in the country—to use a different approach called transdifferentiation.

Since arriving at the University of Arizona in fall 2025, a major focus of the Rhine lab has been generating neurons that retain features of aging—creating a powerful new platform for collaboration with Buchan’s lab.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

Rather than reverting cells to a stem-cell state, the Rhine lab converts donor skin cells directly into neurons.

“By skipping that stem-cell stage, the resulting neurons retain features of aging,” Rhine said. “They look and behave like old cells.”

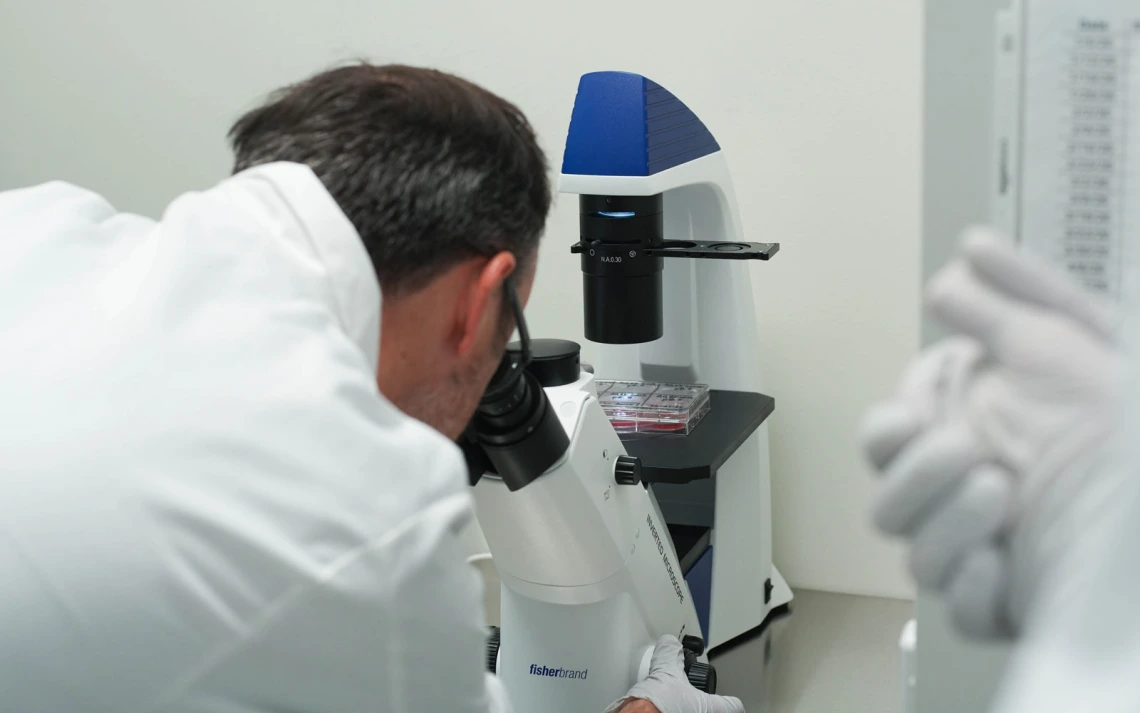

Using a highly specialized technique called transdifferentiation, Rhine and Buchan can more closely study the abnormal behavior of TDP-43, a protein widely recognized as a defining feature of ALS.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

That difference matters for studying TDP-43. While the protein’s abnormal behavior in ALS is difficult to reproduce in neurons derived from iPSCs, transdifferention provides a more reliable picture.

“With Kevin now at the University of Arizona, I was excited because I knew this approach would give us a better physiological model—not only for my work, but for ALS research as a whole,” said Buchan.

As their collaboration deepened, it revealed something larger than a single partnership. ALS research at the University of Arizona was spread across labs, departments, and disciplines, with few mechanisms to bring those efforts together.

Buchan believes neurons generated in the Rhine lab will help reveal how the protein TDP-43 disrupts RNA processing in aging cells.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

From collaboration to community

For a disease as complex as ALS, that fragmentation can slow progress.

“You have clinicians on one side, treating patients. Then on the other side, you have molecular biologists figuring out what’s happening inside the cell to cause ALS,” said Rhine. “And both are so focused on the task at hand, that neither notice the chasm between them. If we want to treat this disease, we need to bridge the chasm.”

Buchan (left) and Rhine (right) see BIO5’s institutional support as a way to strengthen connections and grow a more unified ALS research community at the University of Arizona.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

That gap aligned with a new effort taking shape at the BIO5 Institute. In 2025, BIO5 launched a set of pilot Scientific Interest Groups (SIGs) to bring researchers together around shared problems and provide the administrative and financial support those collaborations need to grow, including one focused on ALS.

“Neurodegenerative diseases like ALS are too complex and debilitating for any single discipline to tackle independently,” said Vignesh Subbian, interim director of the BIO5 Institute. “They require new, integrative ways of thinking.”

For Buchan and Rhine, their SIG extends their collaboration outward, connecting scientific work across disciplines with patient care and making it easier to spot where new partnerships matter most.

“Having institutional support from the BIO5 Institute helps us see where collaborations are possible in ALS research,” said Buchan. “It brings more awareness of each other’s strengths and resources.”

Building momentum in Arizona

The ALS Scientific Interest Group is still in its early stages, but its direction is coming into focus. Buchan and Rhine are reaching out to faculty and clinicians across Arizona, working to raise awareness and making it easier for researchers to find one another around shared ALS questions.

“In many ways, this group mirrors RNA biology, the cell’s logistic network,” said Subbian. “This group will link ALS scientists, ideas, and methods to move discoveries from molecular insights to therapeutic potential. It is a great example of facilitating team-based, convergent science at BIO5.”

The group is already includes a wide range of U of A expertise: a neuroscientist using fruit fly models to study neurodegeneration, an RNA biologist with deep biochemistry experience, and—most importantly—a neurologist who treats ALS patients and is currently the only clinician in Arizona focused specifically on the disease.

That clinical link changes what the group can do. ALS is a rare and often sporadic disease, making patient samples and firsthand clinical insight difficult for basic science labs to access. Bringing clinicians and researchers into the same conversations helps close that distance and better match lab models to the realities of the disease.

The ALS Scientific Interest Group aims to build a coordinated research network in Arizona, forming a closed loop that connects basic research, clinical insight, and patient care.

Lily Howe, BIO5 Institute

Beyond research, Buchan and Rhine envision the SIG as a hub for training and connection. As it grows, they hope to host events, support early-career researchers and clinicians, and help build a coordinated ALS research network across the state.

“ALS is a horrible disease, and we still don’t have effective treatments,” said Buchan. “Every time I hear directly from ALS patients, my heart breaks a little bit, and it motivates me to continue to keep pushing."

With BIO5’s support, they are building a framework that allows discovery and patient care to inform one another in real time, reshaping how ALS is studied in Arizona and potentially beyond.

BIO5 Scientific Interest Groups serve as a “sandbox” for convergence research in biosciences by bringing together people and resources from multiple disciplines in intentional and meaningful ways. The ALS Scientific Interest Group is one of the several emerging SIGs. Stay tuned to BIO5 communications for more updates and opportunities to engage.